That’s so expensive!

How much a houseplant's worth depends on the type of plant, yes, but also the age and the look of it

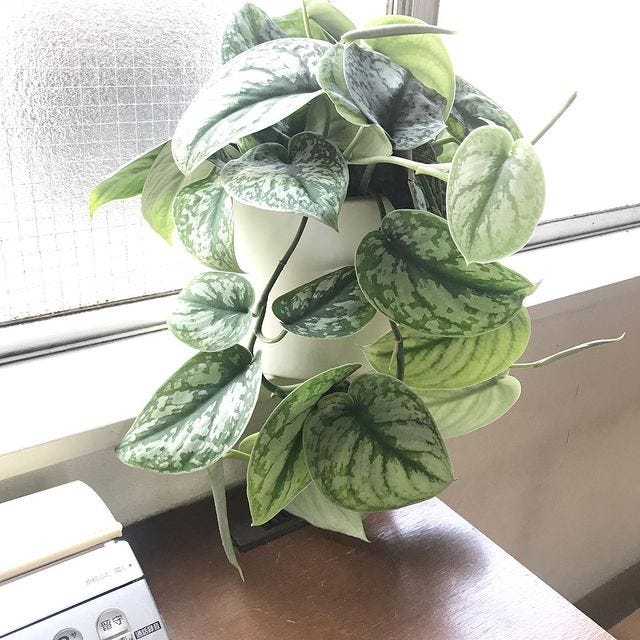

Do these plants look like something you’ll find on sale at a garden centre?

If you’re into houseplants you’ll be no stranger to the idea that price is closely aligned with demand and availability. For en-trend plants, prices can go from a few dollars to thousands and then back to a few dollars for the same plant (read here for one such account). These price fluctuations closely track supply and demand. But this understanding of ’value’ applies to plants assessed according to species or cultivar. This is not wrong, but it’s not complete either. What’s missing is a question that’s just as relevant: how nice of a plant is it?

Notice that this question isn’t primary about the type of plant—it’s about the merits of any one plant taken individually. Obviously both are important. Like buying a used car, you want to know not just the model and make, but also the condition. When plants are all grown in nurseries and sold in shops in the same smallish sizes, cultivated in the most efficient and least interesting form, this question of difference from one plant to another doesn’t amount to much. They are all much of a muchness, like shopping in the can-foods section of the grocery store. But it’s a big mistake to let nurseries lower our plant standards. Indeed, if we are to consider the value of rare and uncommon plants, then more mature and beautifully-grown specimens should be considered as well. Like the plants shown in the photo above, no matter how special or common the foliage, it’s the size and look of the whole plant that matters.

The indoor plants I favor are unique because of how they’ve been grown. To me, when considering how we value houseplants, this is as important a factor as any other.

The Whole Plant

Think of fabric—the material used to make clothes. There is beautifully-weaved material that’s patterned and textured, with wonderful bright or subtle colours. Fabric like this can be very expensive. But no matter how beautiful or expensive, fabric is just fabric—it’s not a garment. Would you go out for the evening wearing just fabric? Of course not. So when we think about plants we should think garment, not fabric, but usually we don’t.

To see what I mean, we need to think about why a garment is so much more than just the fabric it’s cut from. In a fashion show, for example, the individual fabrics play a role, to be sure, but what we see is the outfit. Even a single article of clothing has many different qualities, the fabric being just one.

Applied to houseplants, these different facets include, first and foremost, the overall presence of a plant. A few weeks ago I visited someone who had a moderate sized collection of sought-after houseplants. Their home was small but not crowded. What struck me most was not how special the plant varieties were, although they were quite interesting—several I had never seen before in the flesh. Most impressive was how well each plant had been grown, cared for and styled. Even the more common plants looked amazing. Which meant that the collection as a whole made quite an impression.

Big or small, common or rare, a plant should be grown to show itself off. This over-focus on fancy foliage can be seen in the image above: we see the lovely variegated ‘fabric’ but we don’t see the plant: a plant is not a leaf, it’s not even a collection of leaves. It’s something much more, or at least it should be. If your own expensive collection of plants looks a bit shabby, this could be the reason—because you haven’t accepted that having great plants requires a greater degree of hands-on attention.

To take a closer look at this idea, and how it relates to ‘what a plant’s worth,’ consider the baby houseplant. As with the small gloriosum shown above, a baby often has nothing much more than a small leaf or two to offer. But the whole plant idea still applies, because little babies in little pots are compact and cute. For this reason they can get away with their lack of impact with regard to size. They have a presence, if only a small one.

As a plant matures, however, a problem emerges. It’s not enough just to have more and more fabric. It needs to be in good shape and it needs organizing—chop, chop. If you buy a pothos and it has only two strands of foliage, are you just going to let it run skinny for miles?

Too often we’re precious with our hard-earned plant growth and don’t want to lose any of it. Or we think it’s harmful or wasteful. Get over it. You need to do something with that growth—and in many cases, what you do, or don’t do, will determine the ultimate merits of the plant, regardless of what ‘fabric’ you’re starting with (plus, you can propagate the cuttings).

Yes, some plants naturally fill out and become lush and beautiful all by themselves. But usually this is not the case. I give some examples below, but the first point to make is that, for the most part, plant nurseries sell fabric, not garments. Nurseries sell in small sizes, usually over-potted, and often in low budget, rubbish soil. So don’t think of your newly acquired plant as a finished product, cultivated to naturally mature into a perfect specimen—it’s not. Again, it’s fabric: you the proud owner have to grow and tailor the plant.

One example of the need to turn your fabric into a garment are ficus trees, including the rubber plant (ficus elastica) and the fiddle leaf (ficus lyrata). Nurseries typically grow these as tall, slender sticks that have no branching and forever need a bamboo stake to hold them up. People buy them and take them home, grow them until they hit the ceiling, or until they fall over and snap into two, then scratch their head about what to do next. The image below shows this scenario, and you can read about it here.

What nurseries won’t do, but you should, is chop them back. Ficus trees of this sort should be bought when they’re relatively small and inexpensive so they can be cut back without losing much height. When you do this, several things happen. First, as shown in the image above, if done during the warmer months when the plant’s growing, it will usually branch out in a few areas below the cut. Now, as the plant grows taller, it’s going to be bushy instead of being a bean pole. A second thing that happens, and one that we don’t often think about, is that the tree doesn’t grow tall nearly as fast. This sounds like a bad thing, and for some it will be. If we’re only interested in height, regardless of the look, don’t cut it back until you have to. But if you want to grow a tree that can actually stand on its own one leg, you have to cut it back. Think of it this way: when there is only the one leader, headed straight toward the ceiling, all growth is vertical—it grows tall too fast; by contrast, when you have branching, most of the growth is not vertical. As a result, as also shown above, the trunk thickens. Why? Because several branches of growth in the upper part of the tree translates at the base of the tree into several units of growth, rather than just one. Trunks take time.

Now that you have the habit of cutting it back, you can keep doing it. I have a rubber tree I’ve cut back dramatically three or four times (shown below). It’s now about 1.5 meters tall, and the trunk is about fifteen centimeters diameter. If it’d been allowed to grow tall, it would probably have two or three branches, instead of a dozen, and it would be five meters tall. But of course it wouldn’t be five meters tall, because who has room for that!

The challenge of fashioning your houseplant into something beautiful as a whole means viewing it as more than a collection of foliage. Height is great, but bushy is even better. A plant that’s full gives one the natural impression of health and vigor, and seeing this in your home environment is a natural source of fulfillment. But it takes more than just watering, just as it takes more than just being voluminous. The medium-sized pellionia pulchra shown below is striking, especially in person. It has been pruned back to create more shoots and thus become bushier, but it has also been grown in the appropriate conditions for the species.

The three tricks to tailoring nice plants are proper watering, vigorous pruning, and placement in the correct conditions (lighting and humidity).

So How Much is a Plant Worth?

What then does the fabric analogy have to do with what a plant’s worth? First, let me say that the real answer to this question is the same as for the question of how long is a piece of string. There is no real answer. Second, with this in mind, let me say that the fabric notion doesn’t have everything to do with it, but it’s part of the story.

It all begins with my prejudice that a beautifully grown, ordinary houseplant makes for better viewing than beautiful foliage on a scraggly houseplant. You can buy exotic and expensive plants—with their large leaves, dramatic fenestrations, crazy colours, or unusual textures—but you’re still confronted with the problem of growing the plant so it looks nice. The perfect example of this, for me, is the variegated monstera deliciosa. Whatever type of VM you have in mind, it’s my view that, as it grows large, it gets uglier. While the leaves are beautiful and often striking, the plant itself can be noisy and unruly as it matures. As a larger specimen, three things are happening all at once that come into conflict. There is the dramatic patterning in the leaves, there is the air roots and clumsy shape of an epiphyte plant that needs a tree but doesn’t have one, and there’s the fenestrated leaves. There is too much going on to paint a pretty picture. So here’s a case where, to create the best ‘garment,’ many smaller units have more value than one large one, both financially and aesthetically.

Whether you agree or not, the point here is that the plant as a whole is a different thing than the particular features it has. Applied to the question of what a plant’s worth, I put as much value on maturity and style as on the exotic qualities of the plant. The reason for this is simple: as noted above, when living with plants, it’s the whole plant that you experience. Fancy foliage, or chasing down every new and thus expensive cultivar just because it’s new, is overrated.

The tall dracaena marginata shown below offers an example of a mature, common plant. It’s an expensive plant, to be sure, but it’s expensive because of its maturity and styling, not because it’s made of unusual ‘fabric.’ As with the cut-back/ reduced ficus lyrata above, choosing age over fancy foliage is, in my view, money well spent.

One aspect of plants that’s not applicable to fabric or garments is that you can grow them. This means that, if you have the time and patience, you can buy small and cheap and make the plant you want. Of course sometimes you have a need for a specimen plant now and waiting three or even ten years is not an option. The approach I’d recommend to anyone building a collection is to take a balanced approach: buy one or a few specimen plants over time to get the ball rolling and then fill it in with smaller plants that will close the gaps over time. Meanwhile, do as I say and not as I do: several plants I have acquired in the past did not fare well because I made false assumptions about how to care for them. So make sure that, before buying an expensive plant, you really know where to place it, how to water it, and how to prune it—whether tiny and rare or big and stylish.

Summing Up

The value of rare specimens are mainly a product of supply and demand, as noted (and as discussed in the Dirt Wise article here).

The focus here has been to shift your attention away from fancy foliage, or the latest cultivars on the market, to focus on growing, or buying, styled, mature plants. These plants can also be hard to find, and may seem too expensive! Sometimes I hear this at MONSTERA, but this is one area where I’d say the customer is usually wrong. Going back to the example of fabric and garments, everyone knows how expensive clothes can be, and even fabrics can cost a small fortune by the meter. Same for things like quality furniture or even wallpaper—all of which is usually mass produced overseas. Most nurseries sell houseplants that are less than one year old, so they too can be produced and sold cheaply. Buying houseplants, including indoor bonsai, that are several or dozens of years old is a very different animal. When you factor all that’s involved, and that they’re usually ‘locally-made,’ I don’t think they’re unusually expensive at all.

The mistake here is thinking that, because plants are easy to grow and propagate, any commonly available plant should never be expensive. Several mature plants shown above are examples to the contrary. This is like holding up a $150 dollar bottle of wine and declaring it’s just a bunch of smashed grapes. Yes, you may be able to produce the same plant (or wine) over time yourself, and that’s what I recommend. But if you’re buying a beautiful specimen, and you know how to keep it that way, it’s usually a good investment, aesthetically and financially.1 Certainly it doesn’t depreciate like your new $90k Audi.

Again, when buying plants, don’t think fabric, think garments.

A final example are the large, green leaf philodendrons. When young, many of these philos look much alike, yet their prices can differ considerably. The differences in price relate to the fact that some of these tropical plants have a greater capacity to become fine specimens than others; as they mature, some are capable of growing more massive foliage. So unlike the typical scenario, where plants are valued by their scarcity or newness, the reason for price differences here are due to how they will look in the future.