The Wacky, Wily, Wonderful World of Bonsai

Bonsai is a serious craft, full of rituals and rules, and largely irrelevant for everyday plant lovers who like small trees and a bit of fun

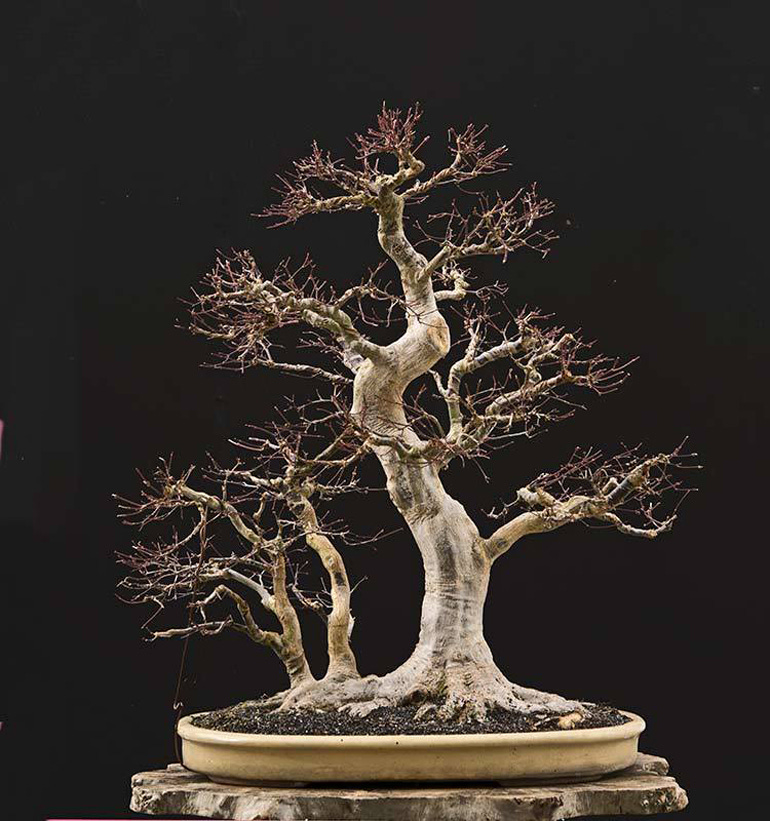

If you adhere to traditional methods of bonsai, you can make a true masterpiece. Like the one shown below from the experts at Bonsai Mirai in Oregon. Some say it takes only about three generations, so make sure you have lots of offspring. Oh and one other thing: if you speak English, you’ll need to learn some Japanese as well, and probably even your kids. Don’t be an idiot and say ‘bon-sigh’ like normal people — you have to say it the Japanese way: ‘bōn-sigh’. See, it’s easy. You’re already on your way. Again: ‘bōn-sigh.’

However you pronounce it, bonsai is big these days. But beware. People who do strange things to small trees can sometimes be a bit strange themselves — even twisted. Like the Japanese.

But not totally. What the Japanese do usually makes sense — in Japan. They are masters of aesthetics and experts at bending nature to their artistic whims. Horticultural geniuses, you might say. What makes Japan special for me is the depth of their traditions, their craftsmanship, their superior approach to the nature of time, and their quirky and cute modes of expression. So don’t worry about saying ‘bon-sai’ instead of ‘bōn-sigh,’ because the Japanese would be a last people on Earth to hold it against you. Which is no surprise given how little deference they show to any other culture’s language.

Unfortunately, when bonsai methods and aesthetics were taken to America and elsewhere, none of their whimsical, elastic playfulness was brought along with it. In English, ‘bonsai’ translates into a slavish adherence to both trees and the technical rules for manipulating them. As the phrase, ‘bonsai widower,’ suggests, bonsai is serious business, dominated by men.

Seriously though

Many of the great stars of bonsai practice today, outside of Japan, actually did several-year bonsai apprenticeships in Japan. They painted a lot of fences, and had to learn Japanese too. So no wonder we bonsai upstarts have to learn to say, not just ‘bōn-sigh,’ but also ‘o-negai shimasu’ and ‘arigatō gozaimashita.’

And in some ways this makes sense. Bonsai practice in Japan is a traditional craft and aesthetic, tailored to produce an abstract and meditative mode of experience. If we want to mimic this rarified construction of natural beauty, then we too need to be dead serious about our trees.

But must we all? Do the rest of us have to paint the fences and embrace all the stoic, austere, and even pedantic seriousness that makes bonsai what it is in Japan (and elsewhere)? Of course not, and I can tell you why: even the Japanese don’t think this. The simple art of the small tree in decorative pots is growing in Japan and pays little homage to the grand masters of bonsai’s past and present. And I’m sure they care not at all.

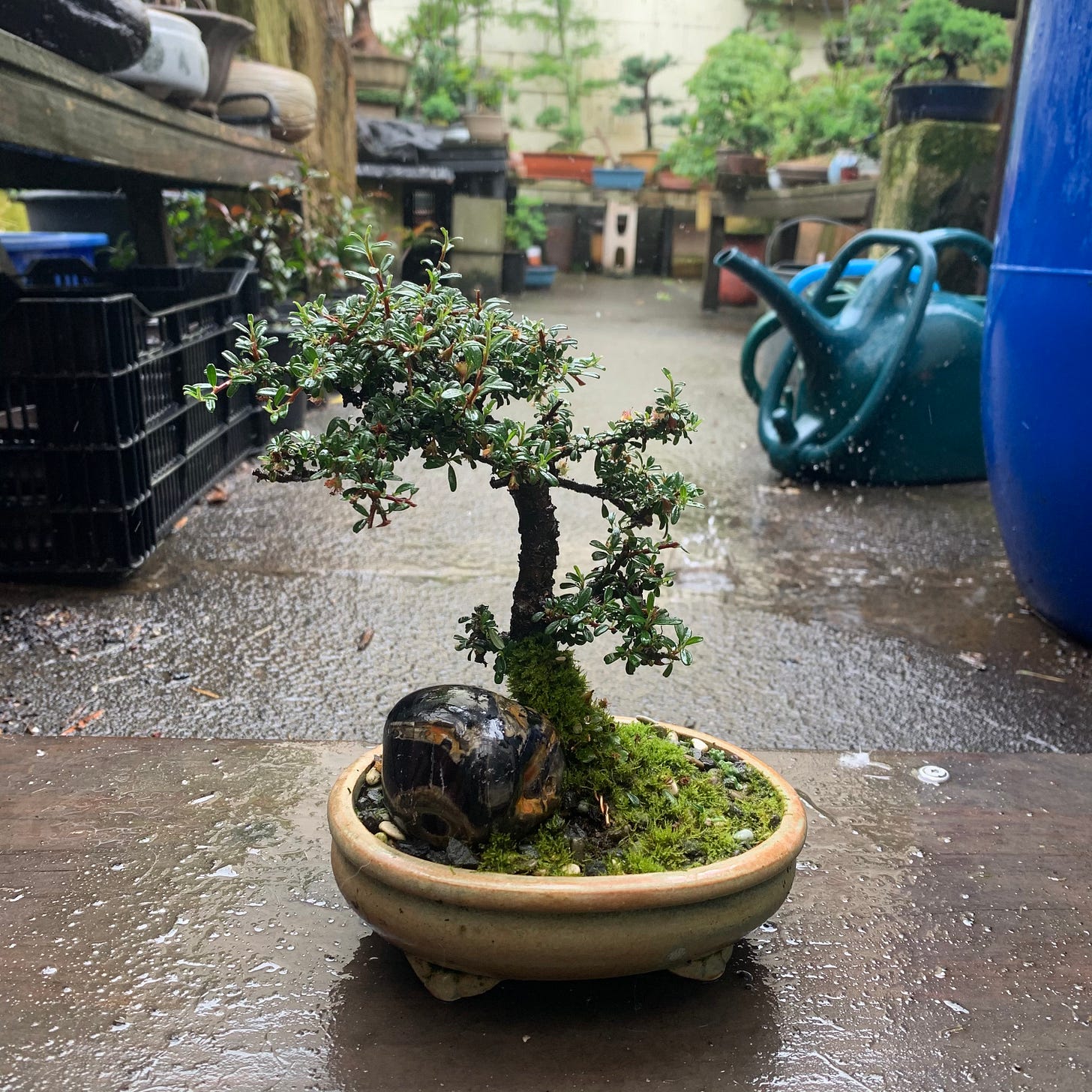

I first came across Seki-Bokka when I was in a small shop in a mall in Saitama City, near Tokyo. As in the image below, the small trees with moss were sold in hand-made pots all made by the same company. This surprised me because the store was just a few miles away from the heart of the great bonsai masterworks in Japan — Omiya Bonsai Village. While others visiting Saitama City at that time — for the World Bonsai Convention — might have come across these trees and dismissed them as ‘sissy’ imitations of real bonsai, I found them fun and intriguing — even beautiful. They were small trees in a pot, like traditional bonsai, but they were also light, whimsical, and simply stylish. And affordable. The professionalized haughtiness of bonsai in Japan hadn’t scared these people off, so why should it scare us?

Some will agree with my assessment of the small trees pictured above; others will see them as a ‘stick in a pot’ — a derogatory expression of bonsai professionals. But seeing is not necessarily believing. For better or worse, those steeped in the practice of bonsai learn to look at, and see, a tree in a way that novices have not. But who’s objective here and who’s prejudiced: the the naive observer or the experienced?

One thing we know about perception is that it’s a movable feast. Whether it’s opera, paintings, people, or architecture, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But this doesn’t quite say it, because the perception of the beholder is itself changeable. To use an extreme but revelatory example, people who experience eating disorders often have a perception disorder in which they literally learn to see themselves as bigger or fatter than they actually are. They see other people accurately, but learn via social conditioning to see themselves as fat. All of which is a fancy way of saying that bonsai enthusiasts can’t exactly be relied on for objectivity. Like an inverted body-image disorder, if you dwell on trunk size long enough, and put a high enough prize on it, any tree of a young age will start to look like a twig.

Meanwhile, what the ‘small-tree’ people in Japan know, and what we in the West have yet to appreciate, is that styling trees in pots is not solely the domain of bonsai and its practitioners. Let me say that again: styling trees in pots is not solely the domain of bonsai and its practitioners. Or at least it shouldn’t be. The bonsai community pushes too much out of the picture to give it all over to them.

This is the hegemony of bonsai, and as I hope to show, for general plant lovers, it’s more burden than blessing.

Can’t get satisfaction

How long it takes to get satisfaction in the bonsai world is an example of how bonsai customs can burden us.

A favourite term in bonsai is refinement, which means improving your trees over time by training them. What it means in practice, however, is that your tree is like a kitchen under constant renovation. It’s never finished and it’s often under the kind of construction that leaves it looking ransacked. All you wanted was to cook a meal and now look at what’s happened. Remember the putative, three generations it takes to make a great work of bonsai? Do you really want to wait years to appreciate a styled tree? Maybe you do, in which case bonsai techniques will prove useful. Or maybe you don’t, in which case common-sense should be your guide.

Of course, bonsai enthusiasts won’t agree. Small trees in pots is their turf and you’re right to expect them to defend it. Here’s a nice, condescending example, from The Little Book of Bonsai:

So, you may ask, ‘If a bonsai is just a potted plant, aren’t all my house plants bonsai now?’ Before you start thinking that you were a bonsai master all along, remember the difference lies in care and maintenance. Bonsai is a style of plant care, developed into an art form, in which trees, usually 1m (3ft) or less in height, are shaped and styled into small representations of larger scenes found in nature.

Such an attitude is ironic given that, historically, the original concept of ‘bonsai’ in Japan referred not to bonsai as we know it today, but merely to any decorative arrangement involving a plant in a pot. As one scholar writes,

The problem is that the word ‘bonsai’ was not used to refer exclusively to miniature trees grown in pots, their shape deliberately manipulated. In the late Edo period [between, say, 1853 and 1867], all potted displays of plants and flowers …were referred to as ‘bonsai’ … There was no distinction between potted trees and conventional kinds of potted plants and flowers. This can be seen from ukiyoe prints in which a plant seller displaying his wares is seen offering ordinary potted trees and plants alongside what we would think of as ‘bonsai’ today. Additionally, as late as the first decade of the twentieth century, it is not unusual to find tips on growing regular potted plants and flowers in pots in books supposedly about ‘bonsai.’ (ref)

This nineteenth and twentieth century evidence implies, quite significantly, that even in Japan, there was a time not so distant when no horticultural distinction was made between trees versus other plants housed in pots for decorative purposes. Prior to this there was a similar attitude in China. Indeed, few Westerners realize that another, less formal style of representing nature via small trees in pot landscapes persists in China under the name penjing. There is no more reason for those keen on a modest foray into this realm to use the term ‘bonsai’ than the term ‘penjing.’ Both concern the art of styling small trees in decorative pots.

This historical evidence should give us some initial confidence to go forward here with our common-sense approach to ‘small trees’ — and leave the technical complications of the bonsai tradition for others, or at least for later.

The cult of the bonsai

A related way in which bonsai traditions burden us is in the premium they place on size and age. Which is of course why the kitchen is under perpetual construction. Say you show up at a bonsai club with a shapely little pine that caught your eye at a garden centre, what can you expect? Experiences will vary, for sure, but one thing almost certain to happen is your tree will be judged, not for the tidy little tree it is, but for the aged and mature tree it must become — if it’s to be a true bonsai. Why? Because the bonsai tradition is all about cultivating in a small tree the age and character you experience in the massive, mature tree you see out your window. Here is a summary of this attitude, as followed in Japan:

The first step in creating bonsai is to take a young sapling, or even a small tree that has grown for some years in a natural setting, and transplant it to the pot where it will be raised. At this stage the heart of the craft lies in the artisan’s ability to envision clearly what form he would like the tree to take as a mature bonsai, decades or hundreds of years later, and to shape the tree toward that end. In order to realize the future tree thus imagined, the artisan nurtures and protects the tree from day to day. … In order to achieve the bonsai’s final form as it has been envisioned, the grower must display highly polished skills to match the life force within the plant.

This prejudice towards high-skill and aged-beauty permeates bonsai practice outside of Japan today, affecting everything from the soils that are chosen to the reward systems constructed to bind practitioners to traditional rules and practices. Needless to say, this value system leaves no place for a simple, small-tree approach.

Can you paint like Picasso? I didn’t think so. But should that stop you from painting? Even if you have no ambition to build a great Cathedral, should that keep you from being a builder? If you’ve no interest in entering your dog into the Westminster dog show, should you not even bother to have a dog?

One of the faults with the bonsai community is that it knows no bounds. It’s not just too serious and too jaundiced in its viewpoint, it’s also too ambitious for most of us and, consequently, too demanding. The bonsai community has no respect for day-traders — green thumbs who can find pleasure in the small and simple. Which is a darn shame because what could be more Japanese than to embrace ‘kawaii’ and the ethos of small is beautiful. As Lee O-Young explores in his book Smaller is Better: Japan’s Mastery of the Miniature,

.. this is an innate Japanese taste: a form of cultural DNA that to this day informs Japanese people’s creation of products like miniature figures of anime characters and the trinkets they attach to their mobile phone straps (see reference).

Instead of trying to paint the next Rembrandt, we should follow the Nippon trend: while we may enjoy viewing professional displays or exhibitions of great bonsai masterpieces, cultivated over generations, when it comes to our own garden creations, most of us want something more fun and less serious — more playful and less profound. A bit of whimsy can really raise your spirits, after all. In fact, it’s not really just in Japan that a love of small and simple is en trend.

I know from retailing bonsai trees for several years that the vast majority of trees sold are not to bonsai specialists, regardless of whether it’s a tree for $60 or for $3500. Most buyers are everyday people who want a ‘bonsai’ or two to add to their potted-plant collection, whether indoors or out. Many are also bought as gifts.

A friend of mine bought one of my small trees recently - a native pohutukawa. It was about $130. He doesn’t usually go in for wee sized bonsai, but it seems this one was too charming to pass up. My friend has his own proper collection of bonsai trees, which led to this encounter: Not long after buying the little native, an acquaintance stopped by to appreciate his collection. And damned if the visitor didn’t go straight to the small pohutukawa, pick it up, and declare it his favourite. Kawaii!

The emperor has no leaves

To sum up, traditional ‘bonsai’ conventions are ill-suited for those interested in trees, not as a rarified art form, but as a pruned and potted plant to enjoy at their leisure. Just calling a tree in a pot a ‘bonsai’ shouldn’t make it a whole new horticultural category requiring a special set of tools and technical know-how. But that’s what the public has been led to believe. Far better, I think, to keep-it-simple-stupid by approaching the problem like any other task involving a plant, soil, and a pot. Knowledge is required but not special knowledge. Special knowledge is available but not yet required.

Here’s another example of the ‘bonsai’ burden…

Below is a maple, bonsai tree shown with and without its leaves. Maples are deciduous so if you have them, you spend some of the time looking at a barren tree. For many the fine foliage and changing colours are so splendid that it’s worth it. I would agree. Many Japanese maples make the perfect bonsai ‘material.’

Still, I have to ask: which look of the tree do you prefer? Probably the leafy look, I’m guessing, considering this is why maples became bonsai specimens in the first place. But here’s a thing that’s weird about bonsai the Japanese way: they have learned to prefer viewing these trees with no leaves. In Japan and elsewhere, maple bonsai are usually exhibited in Winter, and thus in their defoliated state. If you ask a bonsai expert why this is, they’ll tell you there’s a good reason. A lot of work has gone into developing the main and fine branches of the tree, often with the use of wire to orient the branches — and when it’s covered in leaves, you can’t see this handiwork. Like painting over the wood of a finely dovetailed cabinet. The intricate, fine branching creates a density or compactness in the foliage, which raises the quality of the overall aesthetic. Have a look at the second image above and you’ll see what they mean. Fine branching is called ramification, and you can see it here, along with a nice distribution of primary branches.

At this point you may or may not have noticed that the whole aesthetic has been turned on its head. To wit: if it’s true that all this fuss over branch-placement and ramification is necessary to create a proper, deciduous bonsai, then it follows that this effort will be reflected in the foliage display; otherwise, what’s the point? We don’t need to see the branching because, according to bonsai logic, its virtues are mirrored in the foliage. Something’s wrong.

Clearly, there must be another reason for displaying these trees in a manner that would lead many in the general public to think they were dead.

Say you’re really into hot-rod cars and spend a whole lot of time and money making the engine in your Pontiac look as shiny and spotless as the Queen’s dinner table. Nothing wrong with this and we can be certain you’d want to show it off. Open the hood, let everyone see. So it goes with the desire to display a maple tree in Winter. It’s nothing more than a case of showing off. The means have become the ends — the technical has superseded the aesthetic. Indeed, much like the well-appointed and polished V-8 engine, much of what’s gone into styling the bonsai is not entirely necessary. Chrome manifold covers do not improve performance, they’re just there for show.

Most bonsai enthusiasts will beg to differ, we can be sure, but I don’t think you can deny it: maple trees should be displayed with their foliage. To do otherwise is to forfeit the whole raison d'être for maples as bonsai specimens.

To be fair, though, there’s an aspect of my critique that’s crude. At a car show, everyone agrees your Pontiac needs a hood for the car to look proper and nice. But they also agree that it’s cool to see what’s under the hood. The same goes for the display of bonsai. Serious bonsai people want to show off their well-honed interiors. It makes sense. And herein lies the rub: the vast majority of those who like the aesthetic of a nicely-pruned tree in a shallow pot don’t view a bonsai the way serious bonsai people do. We simple plant lovers want to see-the-forest-for-the-trees. And we don’t want to see our tree, or their tree, naked if we don’t have to. Keep your pants on for goodness sakes.

Get real

While bonsai enthusiasts might bristle over the above critique, general readers might very well think I’m making it all up. In truth, it’s worse than I let on.

If you embrace the common-sense notion that maple trees look better with their leaves on, you can escape the burden of meticulously training a tree to the point that every inch of every branch looks ‘perfect.’ Truth be told, you can buy a Japanese maple at a garden centre and put it in a nice, shallow pot, do a bit of pruning, and voilà, you have a nice bonsai.

The simple ‘bonsai’ below required almost no effort to create, which I suppose, by definition, means it’s not a bonsai. It’s certainly nothing like the impressive bonsai by the well-known artist (Walter Pall) above. But then again, it’s not meant to be. And that again is the point. Not every bonsai needs to be a statement, and not everyone has the time to create one, or the money to buy one, or the stamina to take care of one for the rest of their life. Some don’t even like such ‘awesome’ trees, seeing them as pretentious and ostentatious instead.

Even Walter Pall agrees, I suspect. The reason I relied on photos of his maple tree was because it showed the same tree with and without foliage. But there was another reason: Walter Pall doesn’t actually rely on meticulous methods of one-by-one branch pruning to create his deciduous bonsai. He uses a technique loosely defined as ‘hedge-pruning.’ Which basically means he prunes excess foliage in the Spring much like any sensible gardener would. Yes, an authentic bonsai sinner is in our midst! Now if this sounds like a contradiction, I know what you mean: I just said bonsai practitioners are often fanatical in their methods, only to then say the person who created this masterful maple didn’t use these methods.

But it’s not a contradiction. If you Google ‘bonsai + hedge-pruning’ you can read up on the controversy regarding Walter Pall’s non-traditional methods within the bonsai community (e.g., see here). If you don’t follow the rules set out by the bonsai tradition, you can always rely on the keepers of the faith to call you out, and that’s what has happened.

Remember how I mentioned that many of the ‘rock stars’ of bonsai in the West actually sharpened their shears in Japan? One of these individuals is Bjorn Bjorholm, who, not surprisingly, hates ‘hedge-pruning.’ You could not meet a nicer guy than Mr. Bjorholm, which makes his insistence on all methods being Japanese all the more curious. If you do listen to his podcast below, keep in mind the discussion above — namely, that all this fuss over fine branching, movement, and branch taper is about something that’s all under the hood. His argument is as clear as it is sound, but it’s entirely irrelevant when your maple has its leaves on.

Bonsai is a dirty business

Here’s another way in which a fetish for size and age in bonsai burdens our simple ‘small-tree’ approach: the quest for growth.

The desire for trees that reflect the majesty of age makes bonsai practitioners impatient. You would be impatient too if you thought you had to wait a decade or three to get the bark on your tree in the right shape. Of course this is another irony in that bonsai is commonly hailed as an exercise of slowness. Your bonsai reflects nature and being in nature should relax you and remove you from the worries of the day. But how can it if it won’t grow fast enough! That’s just something else to worry about.

Relax, don’t stress, there’s a solution here: we shall create exotic soil substrate mixtures that accelerate growth, and considerably. The only problem is that these mixes require you to water far more frequently and use fertilizer far more often than ‘regular’ soil. To which you reply: how does this make my life easier, or calmer? It doesn’t, it just makes your trees grow faster. Oh dear.

Of course, even this is not enough. Bonsai practitioners are always on the hunt for new ways to escape from nature and apply magical tonics to their soil-less soils. This ‘search for the holy grail’ in soil science was on full display a few years ago when one of the top bonsai practitioners in the US decided to dose his trees with one of these magical growth juices. Such is the thirst for faster growth that Ryan Neil at Bonsai Mirai didn’t just choose a few average test specimens to experiment on in a controlled study, he wacked his entire collection of 900 or so trees, worth a few or even several million dollars. It was not long before much of the collection began to show signs of ill heath and the experiment had to be halted full-stop.

What a rabbit hole this is. It’s pervasive enough in fact that I regularly experience it first hand. I had, for instance,the pleasure of hiring a young Japanese bonsai practitioner to work at my nursery before COVID sent him packing. I met him several years earlier in Kyoto when he was a bonsai apprentice. I thought it wise, given his extensive training, and my lack of it, to let him do things his way, more or less, and he didn’t disagree. The first thing was to change all my soils. I had misgivings but I like to keep an open mind. He worked studiously and in time he accomplished his goals. The new soils were fine, although I was now watering and fertilising more frequently—except for one thing: these soils were not at all suitable for most people who buy bonsai trees.

What’s the point of using soils that promote optimal growth for a far off, distant goal if the tree dies in a few months because it dries out in a few hours of Summer sun, or grows weak because it’s starved of nutrition. You can argue that this is the fault of poor practice and ignorance, but we still arrive back at my same point: why should day-traders be subservient to bonsai rules when they’re not beholden to the cult of size and age?

The real bonsai artist

One way to deal with your desire for size and age is to cheat, and once again who could blame you. You’re never going to have a sixty year old bonsai when you’ve started at my age. By cheating I mean acquiring mature bonsai stock from wild settings, by permission, or by buying them at a certain age from other bonsai people.

Here bonsai has a somewhat dubious history. In Japan, for most of the history of exhibiting bonsai, it was the owner of the tree and not the actual bonsai artist who got the credit. This made some sense for trees that were so old they had many masters. The credit could be given to them all, perhaps, but it was the Japanese way to defer to the one thing that was certain when any prize was awarded: ownership. To some extent this is a common, class-based phenomena seen throughout the world. In glass-blowing factories in Europe, for example, it was the aristocratic designers who claimed credit for clever and beautiful glass works — works that only the sweating, glass blowers down on the factory floor could ever dream of making. It wasn’t until the studio-glass movement that makers got the credit and profit for their own work.

Sadly, in bonsai today, this practice continues, but without the class component. People buy trees designed to varying degrees by others, maintain them for a few years, and then claim them as their own. In legal terms of ownership this makes sense. But in terms of the bonsai ‘artist,’ it’s questionable at best. As in earlier times, the problem of attribution can be complicated: who did what and when? When does a living, changing thing shift from being the creation of one person to another? There is no absolute answer.

But to say the line is blurred is often a cop-out. I have bought wild-grown trees that have little articulation in their design — they are full of potential, but that potential is not at all realised. In such cases it’s usually easy to put your own stamp on the tree over time. I also own some old trees where I have done so little work that the original owner would recognise their tree in a second. It would take at least another decade or two, with some significant branch work, to imagine otherwise. In these cases, it’s a dubious idea to say you’re a bonsai artist and then claim credit for someone else’s work. You are more the steward than the artist, and the provenance of such trees should be documented and made clear.

I would love to buy a Picasso or even a Rembrandt and claim it as my own work of brilliance, if I had money to burn. But I’m not sure I’d ever forget removing the signature. In the wild, wacky, and wily realm of bonsai, however, the habit of appropriation is nearly as strong as the habit of forgetfulness. I’m not claiming most bonsai ‘artists’ are standing on the hidden shoulders of giants. But I am suggesting that the practice is so accepted that it’s easy to delude oneself into believing a beautiful tree that belongs to you actually exists in the world because of you. Sometimes it just ain’t so.

But I digress. In the simple, small-tree world we don’t have any such worries. The trees are small, the problems are small, and the liabilities are even smaller. And while my remarks might seem antagonistic towards bonsai, it’s my belief that a gentler, non-‘bonsai’ introduction to working with trees might actually be a more effective way of yielding future practitioners. As one Japanese historian writes:

There is no need to reject or sneer at the ‘light’ forms of bonsai that young people and women often prefer these days. These forms, after all, may one day provide fresh vigor and direction to what we today consider to be traditional bonsai. If a tradition cannot display the courage and vitality to accept new, external stimuli, constantly adapting in response to this input, then it will not be able to continue as a tradition.

More on bonsai in the Dirt Wise articles below.

Fantastic write up, really enjoyed that thank you very much. Well articulated on a subject not easily explained.