From the Shade House to Your House

The Horticulture of Healthy Profits Instead of Healthy Houseplants

Editor’s note: Let’s categorize this one under gripes and pet peeves…

As D. G. Hessayon, author of The House Plant Expert, wrote years ago, “the charm of houseplants may be universal, but many millions are allowed to die needlessly each year.”

Sad. And no less true today.

There are many reasons why few houseplants grow on to become healthy adults. If you look for reasons online, you’ll find answers like “overwatering” or “inadequate light” or “not enough humidity.” But there is another reason, and one you probably never think about: the grower.

Just as makers of foods, or manufacturers of cars, vary in the quality of their product, so do the wholesale nurseries that grow houseplants.

So let’s look at a few of these “less than best” practices and how to avoid or overcome their ill effects.

(1) Overpotting

Most plants delivered to our retail store are in pots that are either too big or way too big!

Nurseries usually base their wholesale prices on the size of the plastic pot; the same size plant will be more or less expensive depending on the size of the pot. This makes some sense. But it also leads to the situation where a nursery can make more money by putting a small plant in too big a pot.

So why do they do this? And why is it a problem?

They usually do it, not as a scheme to rip us off, but because they are sending the plant out too early, before it’s as mature as they initially intended it to be. When plants are in low demand, you might get a bargain because the plant sat in its pot and grew extra large before being sent to the retailer. But much more likely these days is the case where there is high demand, and to meet that demand, the plant is sold smaller, and smaller, and smaller… but always in the same size pot.

We get ficus rubber trees delivered, for instance, that once arrived a meter tall but now arrive half that height—but in the same damn pot. The root system will be half the size, too, so there’s a lot of soil that has no role to play. It doesn't even look proper, because the proportions are wrong.

Now I know what you’re thinking: this should be no big deal because a big pot will encourage fast growth. Under ideal conditions, this might be true. But the ideal conditions were left behind at the nursery, where watering is plant-specific and machine controlled, and where the humidity and heat create a fast-growing, intensive-care environment. At your house, the ICU is long gone. What is more, because the plant was grown in a shade house, it can’t be put in the warm sun (more on this below). So now we have a shade-only plant with too much soil and too few roots to drink all that water in all that soil. When root rot sets in, the plant owner doesn’t realize their plant may have been doomed from the start.

If a plant is dwarfed by the pot, too big; if the plant is tipsy in the pot, too small.

Before moving on to the next topic, let me say more about what I mean by a pot having too much soil. (Skip if bored)

Simply put, unless a plant is root-bound, the smaller the pot is, the better.

This is counterintuitive, but true. As you know, soil anchors the plant and creates the environment for nutrients and water delivery, including oxygen. But any soil in the pot that exceeds the reach of the roots cannot provide these things. Instead, this surplus soil becomes a reservoir for holding water and for insulating the roots from the external heat they want and need. Naturally, there needs to be some excess soil, since the plant needs to grow. But once you go beyond a modest margin for this, you impede growth by creating a cold and soggy environment that’s ideal for only one thing: killing plants.

When you are faced with this situation, don’t be afraid to remove the pot after watering and see how well-established the roots are. If a heap of soil falls away and a tiny root ball is left behind, there is way too much soil. Do any of four things: Take it back and ask the retailer to sort it out; repot it into a smaller pot; remove some soil at the bottom and repot it lower in the plastic pot; or keep it as it is but make a special note of not watering it until as late as possible. Just remember: all plants need to be fully watered once they’re ready to be watered.

Don’t buy plants sold in pots that are obviously too big.

This applies to succulents and cactus as well, as they need even smaller pots.

(2) Shade House Blues

We can’t blame nurseries for growing houseplants in shade houses. These structures provide for shelter, heating, high humidity, and controlled watering. All these factors speed up plant growth and produce near-perfect (looking) plants. The problem comes when the plant leaves the shade house for the real world: your home.

Here are some examples of issues that arise.

Maybe you have a sunny house? But shade plants don't like direct sun. What to do? One thing you can do is buy sun-loving trees or cacti or succulents—but that might not suit you.

As it turns out, there are a lot of houseplants that burn in the sun but also thrive in the sun. Fiddle-leaf ficus trees, rubber trees, monsteras, and some philodendrons are but a few examples that do well in sun, but only if they have a history of growing in the sun in the first place. Houseplants you buy that burn in the sun may be fine in the sun later, so long as you’re willing to grow the plant on until it has new, sun-adapted foliage (you can remove the damaged foliage later).1

The main point here is that shade houses create shade-house plants, so getting them happy in your house requires keeping this in mind.

Another example: a humid shade house can grow a variety of lovely plants that do well in high humidity but are prone to destructive insects when moved to dryer pastures. Certain calathea and alocasia species are examples of plants that are often overtaken by spider mites in static, dry air. Many of these plants look great for a while but ultimately are not suitable for the indoors.

And a third example: flaccid foliage. Some plants like the ficus fiddle-leaf arrive at garden centres with droopy leaves that won’t stand up and are prone to damage. This applies specifically to newer growth. This happens because the growth has happened so fast the plant foliage doesn’t have a chance to harden off as it grows. To avoid overlooking this and related issues, always inspect the growth tips of plants to ensure they’re healthy and strong before buying.

(3) What Kind of Soil Is This?

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that many nurseries use the cheapest possible “soil" that works for their conditions. The emphasis here is on "their conditions," which are quite different from the ones at your place. As just noted, these include high heat and humidity, and controlled watering. But there is another issue: they won’t be growing the plant for very long. This is important, because when a soil has a short lifespan, it’s the buyer of the plant, and the plant itself, that pays the price.

At our plant store and nursery, we mix up soils that contain a modest portion of compost plus other ingredients that ensure drainage—like vermiculite, perlite, small orchid bark, and pumice. These added ingredients make up the majority of the soil volume, but are far more expensive than basic substrates like coco-fibre. That’s why nurseries rarely use them.

When cheap substrates are used, two problems often arise by the time someone buys the plant and takes it home…

The first problem has been noted, which is that cheap soils don’t last. They compact, disintegrate, and sometimes form into a ball of concrete. If you have spongy soil that seems to be sinking lower and lower in the pot, or clumping and falling out, replace it. Same if the soil solidifies and shrinks in the pot when it’s dry (water thoroughly before repotting).

The second is that cheap soils are often ill-suited to sustain life outside of the shade house, even short term, because they don’t rehydrate well. At home, you don’t have drippers on automatic timers. Instead you probably water intermittently, like once a week. Let’s say you've done a good job and waited until your Fittonia, Calathea, or Pothos is largely dry. But now the soil has probably become water-resistant, meaning you struggle to get water to all the soil and roots. Sometimes the soil is so bad you have to soak the plant for hours just to get it rehydrated.

How do you know when there's a problem? When a plant is mostly dry and ready for watering, it should be light. After watering, it should be noticeably heavier. The soil should be free-draining but it should still hold enough water that you easily notice the difference. The problem with cheap soils is that it becomes harder and harder to achieve this saturation, even shortly after buying the plant.

Coco-fibre is the classic example (see below). Like some other substrates, coca-fibre compresses over time and basically becomes a sad place for roots to grow. You can compress it further, or you can remove some of it, and then add proper soil, but it’s best to bare-root the plant and start over (see third image below).

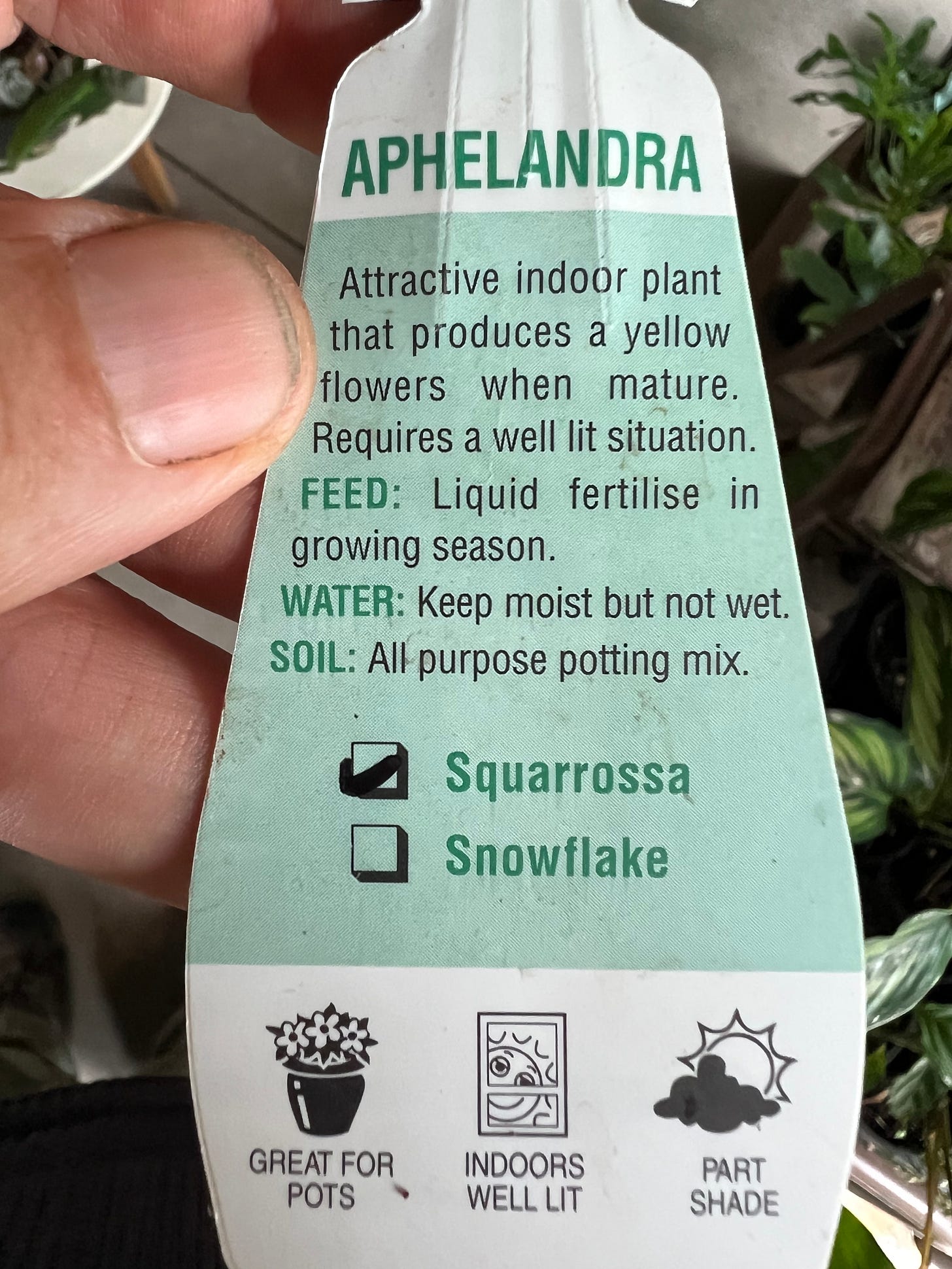

(4) Plant Tags

Plants tags might seem like a minor issue, but tags are the only instruction manual you get for your plant. Making accurate and more informative tags is a missed opportunity.

These plastic tags usually do one thing well: they tell you the name of the plant. They usually also provide information about light and water requirements. Often, both of these are problematic.

Consider the advice of “keep moist but not wet.” Well, you don’t really want to keep any houseplant wet, so that’s not really very specific. "Keep moist" is also problematic because that’s hard to do unless you have drippers. Remember, if you’re watering with a watering container, the vast majority of houseplants need to dry out before watering, and once you do this, the idea of “keep moist” makes no sense. “Water thoroughly once dry” is not perfect, but at least it’s moving in the right direction.

Are these the only two choices for watering: wet or moist? Definitely not. For the Aphelandra plant, for example, the tag might say: “dry out between waterings.” Or even better: “water when wilting.” This is not an easy plant to keep in tip-top shape, as it’s too easy to overwater, especially when overpotted. The info on the tag should reflect this attribute of the plant.

As for light requirements, what does “part shade” mean, exactly? I see this on a lot of tags for plants whose foliage will instantly burn to a crisp in regular sunshine (at least in New Zealand)—because the foliage was raised in a shade house.

My opinion is that plants should be designated with their own minimum and maximum light requirements: If a monstera deliciosa has been grown in a shade house, it should be rated as moderate to bright light. A ficus fiddle leaf grown in the sun should be rated full sun to bright shade. A heart-leaf philodendron should be rated bright shade to low light. Is this asking too much?

There are other things tags could also tell us.

They could state that the plant foliage will burn in the sun (but can be regrown in the sun if necessary—although this applies only to some plants).

They could tell us the plant will likely need to be cut back dramatically to stay looking nice, like the Tahitian Bridal Veil or Callisia Repens (bubbles plants).

They could also tell us that if the leaves are dropping it means there’s not enough light (e.g., ficus fiddle-leaf).

Finally, plant tags could/should tell us when plants are easy to care for (monstera del.) and when they’re not (fittonia).

(5) Plant Specials

Last and least, watch out for plant bargains.

We buy from a nursery that likes to put multiple small plants of the same kind together in jumbo pots, probably because they have too many of them. Then they offer it as a large specimen. The problem is that it’s not a large specimen! It’s a bunch of baby plants poorly repotted together as one. The roots are in tiny balls, so when you try to water them, the water goes everywhere but to the roots. Diabolical.

This is an example of why you should be wary of some plant specials, whether from the nursery or the retailer. Sometimes it really is a bargain, but make sure you look under the hood.

Final note:

Plant nurseries are businesses. If you know what to look out for, you can identify those businesses that are committed to putting healthy plants ahead of healthy profits.

Avoiding sunburn is not about acclimating your plant to the sun. Acclimating is not the right word here because in these examples the foliage does not acclimate—it burns and always will. Only the new foliage adapts. Acclimation may apply to plants like ficus Benjamina, however, where the tree may drop leaves to acclimate to a darker or sunnier spot by growing new ones.