Living in Tissue Culture

Does it matter if your prized houseplant was born in a test tube and never existed in nature?

People love to collect… all kinds of things. A fake, a replica, a restoration, a real antique: these classifications matter—sometimes a lot. We don’t want to pay a small fortune for something and get emotionally attached to it only to find out it isn’t what we thought it was. If a fake piece of antique furniture such as a chest of drawers displays a similar degree of craftsmanship as the original, and is perhaps in better condition because it’s newer, we might raise its standing to that of a copy or a replica. But it will still never compete with the real thing. Antiques are all about where they came from.

It’s similar for art: no matter how hard it might be to tell if a work is a forgery, or perhaps done by a lesser-known figure than hoped, the value drops, both financially and emotionally.

Origins matter.

These thoughts regarding the provenance and history of antiques and other collectibles are not controversial. But what about your beloved houseplants? Have you ever thought about them and their origins? What if you spend big on an exotic looking beauty only to discover it’s basically a fake? It’s not fake in the sense that it isn’t real—it’s alive and growing (or so we hope). Rather it’s fake because the very attributes that give the plant its specialness are not original to the plant—they are human-induced, not nature-made. Think Frankenstein in a shade of green.

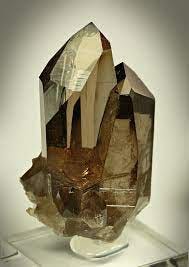

Another useful comparison to houseplants involves the selling of semi-precious stones like smoky quartz (shown below). These quartz crystals are more sought after than their colourless cousins because they’re less common and because the smoky brown translucence has a certain beauty and appeal. Due to their higher value, it’s common for those in the wholesale business to irradiate clear stones and sell them on as smoky quartz. Buyer beware.

This example is interesting for two reasons: One is that the process producing the sought-after attribute is the same in both cases; the only difference is that in one case the irradiation comes from a natural source (during the rock’s formation), whereas in the other case, it’s created after-the-fact, or artificially. Despite the common underlying cause of the smoky look, knowledgeable buyers of these stones will pay a higher price for the natural type, and turn their nose up at the other. Again, despite the fact that the two types are materially identical, value is placed on whether the process occurred naturally (probably for reasons involving our desire for rarity).1 A similar case exists for ‘man-made’ diamonds, which fetch less money than ‘natural’ ones.

The crystal example thus lends an easy comparison to the houseplant, but one that seems never to be made. If what makes our houseplant special is a result, not of the evolution of the species, but of modern laboratory manipulations, do we perceive it in the same way? Should we?

A thought experiment:

Let’s say you have saved all your money and instead of buying a houseful of rare houseplants you decide to buy something even better: a plant-DNA remixer. This is a mutagenesis device that, with a bit of practice, can turn any plant’s offspring into a designer houseplant. There’s a variety of colour options and you can introduce various types of variegation. You can even do things like shorten nodal distance, or alter leaf size and texture. It’s a pretty amazing machine, to be sure.

As you unwrap your new machine and read the operator’s manual, a funny feeling starts to well up inside you. Slowly this anxiety forms itself into an unsettling question: what’s the point? If you can create any plant design by a mere flip of a switch, or turn of a knob, is it really special any more? If it’s a product, not of nature, but of something you first saw on the starship ENTERPRISE, can it really be rare, or unique? ‘Hmmm…,’ you wonder, wallowing in a new state of confusion, ‘what makes a plant special?’

An unnatural beauty

Two plants I think of when I wonder about the meaning of lab creations are the Thai Constellation Monstera and the Philodendron Birkin. Both are offsprings of laboratory manipulation propagated en masse via tissue culture, one from Thailand and the other from China. They are not quite the same, however, in that the Monstera is a more stable mutation than the Philodendron seems to be. For whatever reasons, including how they are grown, the latter seems capable of various forms of reversion—sometimes growing into the Rojo Congo it derived from, sometimes losing all its stripes and becoming like a Green Princess, sometimes making all white leaves, and sometimes doing some or all of the above as in the photo above.

Regardless of these differences, these two examples raise the same question of whether they are, or were, worth paying extra for? Which is to say, or ask, will these plants persist as anything other than average plants in the future?

As I suggested in a previous Dirt Wise article, the quest for exotic foliage is a fad, and an unsustainable one. Baring the actual arrival of a true plant-DNA remixer, there are limits to what laboratories can do. In fact, with so many plant lovers on the lookout for naturally-occuring, sport mutations—like the one shown in the first image, or the one shown below—it’s possible that natural lines of variation might outpace ones from the laboratory. All of which raises the question of what’s the difference? Is there a difference?

Artificial selection

Plant manipulation is a thing of the future, but also the past. From grains and vegetables to roses and orchids, artificial selection and hybridisation have long been used to cultivate new plant creations, whether to serve our basic needs or our desires.

If you have a Golden Pothos, a Marble Queen, or a Monstera Albo Borsigiana, you can cut back the stems with less desirable foliage to encourage the look you prefer. If you then propagate these stems via cuttings, you are engaging in the practice of artificial selection. And why not? There is nothing deviant about cultivating your own plants.

What differentiates the laboratory methods from these just described is the process. When you cultivate plants you are acting upon what the plant offers: variation is the mother of all evolution, and you are responding to the plant’s natural variation. It is only ‘artificial’ because it’s you rather than nature doing the selection. The end result is still the product of nature.

In the laboratory this is rarely the case. It’s one thing for a nursery worker to notice a sport mutation in one of hundreds of Ficus Lyrata trees growing in a shade house in The Netherlands (which led to the development of the Ficus Bambino). It’s another thing when a Birkin or a Thai Constellation appears in a single laboratory that no other laboratory can successfully replicate. What methods are employed are not exactly secret, but they are not exactly known either (another example). And as the Birkin example shows, they certainly are not a reflection of nature.

This is not a GMO argument because these are not foods, although there is a whole other set of questions raised here regarding the rewilding of laboratory specimens. In fact, this is not an argument at all. You cannot legislate taste any more than you can define beauty. But it does bear thinking about…

What does make a plant special?

Diamonds are an exception here because their rarity is itself artificial, except in the case of ‘pink’ diamonds.